Introduction

"Being present" is more than a wellness catchphrase. Over the past two decades, mindfulness has moved from contemplative tradition into mainstream psychology and medicine, with a growing body of peer-reviewed research examining what happens when we train attention on the present moment without judgment. This article summarizes what reputable online scientific sources—including Nature Human Behaviour, Nature Reviews Psychology, and systematic reviews in PMC and MDPI—report about the mechanisms and benefits of present-moment awareness, so you can understand the science behind the practice.

What "Being Present" Means in Research

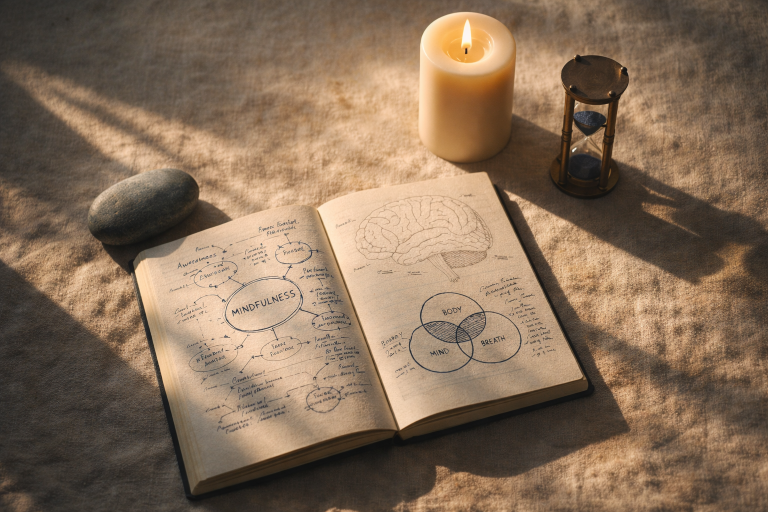

In the scientific literature, mindfulness is typically defined as the practice of paying attention to present-moment experience in a sustained, non-judgmental way. Mindfulness-based interventions aim to foster greater attention to and awareness of what is happening here and now: sensations in the body, the breath, sounds, thoughts, and emotions, observed without trying to change or judge them. This orientation contrasts with habitual rumination about the past or worry about the future, both of which are linked to anxiety and low mood. Being present, in this sense, is a trainable skill that can reduce the grip of automatic, reactive patterns.

Large-Scale Evidence: Stress Reduction and Mental Health

A large randomized controlled multi-site study published in Nature Human Behaviour (2024) found that self-administered mindfulness interventions significantly reduced stress in participants. The study design allowed researchers to conclude that people can benefit from structured mindfulness practice even without in-person instruction, which has implications for accessibility and scalability. Another randomized controlled trial, examining a brief online mindfulness intervention among university students, reported significant reductions in depression, rumination, and trait anxiety after 28 days of practice. Together, these and similar studies indicate that devoting regular time to present-moment awareness can produce measurable improvements in stress and mental health, often in a relatively short period.

Systematic reviews support a broad range of benefits. A comprehensive review of 44 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, published in PMC, analyzed 336 RCTs and over 30,000 participants. It found that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) showed superiority to passive control conditions across many outcomes, with effect sizes ranging from small to large (approximately 0.10–0.89). When compared to active controls and evidence-based treatments, MBIs were typically similar or superior in effectiveness. Benefits have been documented for psychological distress, depression relapse, anxiety, chronic pain, addiction, and behavioral regulation, among other areas. This does not mean mindfulness is a cure-all, but it does suggest that the practice of being present, when taught and practiced consistently, is associated with meaningful change across multiple domains of health and well-being.

How Being Present Works: Cognitive Mechanisms

Why does focusing on the present moment help? Nature Reviews Psychology (October 2024) proposed the capacity-efficiency mindfulness (CEM) framework to explain how mindfulness training affects cognition. Rather than expanding total cognitive capacity, mindfulness appears to work by reducing interference: it minimizes the impact of mind-wandering and negative affect that otherwise disrupt cognitive control and task performance. In other words, we do not necessarily get a bigger mental "tank"; we get better at not leaking attention into rumination, worry, and self-criticism. Training in present-moment awareness seems to help the mind spend less energy on unhelpful mental habits and more on the task or experience at hand.

Neurobiological research aligns with this picture. A 2024 systematic review in Biomedicines (MDPI) examined neurobiological changes induced by mindfulness and meditation, documenting physical and physiological changes in the brain and body associated with practice. Such findings suggest that regular practice can support not only subjective well-being but also measurable changes in brain function and structure, which may underlie improved attention, emotional regulation, and stress resilience.

Practical Implications: What the Science Suggests

The research does not prescribe one "correct" way to be present. It does suggest that:

- Consistency matters. Brief, regular practice (including self-administered and online formats) can yield benefits; you do not need long retreats to see effects.

- Present-moment focus is the active ingredient. Interventions that train sustained, non-judgmental attention to the here and now are the ones most often studied and supported.

- Benefits extend beyond relaxation. Being present is linked to reduced stress, better mood, improved focus, and in some studies, better pain management and behavioral outcomes.

- Cognitive efficiency may improve. By reducing mind-wandering and emotional interference, mindfulness may help you think more clearly and perform tasks with less mental clutter.

Applications Beyond the Cushion: Work, Relationships, and Daily Life

Mindfulness research is not limited to formal meditation. Studies have examined mindfulness-based programs in workplaces, schools, and military settings, with benefits for stress, focus, and interpersonal behavior. The same capacity trained in sitting practice—noticing where attention is and gently returning it—applies when you are in a meeting, in a conversation, or doing a routine task. When you notice you have drifted into planning or worry, you can acknowledge it and come back to the present. That repeated return is what the literature suggests builds lasting change. Individual differences matter: effects can vary with baseline distress, personality, and the type of intervention. Still, the overall picture is that present-moment awareness is a generalizable skill that can support well-being across contexts.

What Being Present Is Not

The science also clarifies what is not required. You do not need to empty your mind, achieve a special state, or sit in a particular posture. Mindfulness-based interventions typically teach observation of whatever is present—including thoughts, sounds, and body sensations—without trying to suppress or change them. The practice is in the noticing and the returning, not in the absence of mental activity. That makes it accessible to people who assume they "cannot meditate" because their mind is busy; a busy mind is exactly what the practice is designed to work with.

A Simple Practice: Anchoring in the Present

Research often uses the breath as a primary anchor. Set a timer for 5–10 minutes. Sit comfortably, close your eyes or lower your gaze, and direct attention to the physical sensations of breathing—at the nostrils, chest, or abdomen. When the mind wanders, notice that it has wandered, and without judgment, return attention to the breath. This cycle—focus, wander, notice, return—is the core skill. Repeating it regularly is what studies suggest can support stress reduction and cognitive benefits.

Integrating the Science Into Your Life

You do not need special equipment or a particular environment to begin. The same mechanisms that researchers study—sustained attention, non-judgmental observation, and the gentle return of focus—can be practiced at home, at work, or while traveling. Many of the studies that show benefits use self-administered or digital programs, which means that apps, audio guides, and written instructions from reputable sources can be sufficient to get started. The key is to practice regularly rather than intensely. Researchers have not identified a single "best" length of practice; what emerges from the literature is that consistency over weeks and months matters more than the duration of any single session. If you can only manage five minutes on a busy day, that still counts. The aim is to strengthen the muscle of present-moment attention, and that happens through repeated practice rather than through rare, marathon sessions. Ten minutes most days is a realistic and evidence-based target for many people. Over time, you may notice that you are less carried away by worry or rumination and more able to stay with the task or conversation in front of you. That shift is what the science of being present is designed to support.

Reflection Prompts

- When I am lost in thought about the past or future, what do I usually miss in the present?

- What one situation this week could I approach with full attention—no phone, no multitasking—and what might change if I did?

Conclusion

The science of being present is robust and growing. Large randomized trials and meta-analyses indicate that mindfulness-based interventions can reduce stress, depression, anxiety, and rumination, and that these benefits may arise in part by reducing cognitive-affective interference rather than by expanding raw cognitive capacity. Neurobiological research suggests that regular practice is associated with measurable changes in the brain and body. You do not need to clear your mind or achieve a special state; you need only to train attention on the present moment, again and again, with patience and consistency. That is the practice the research supports, and it is accessible to almost everyone.

To bring this science into daily life, see Your Essential Mindful Living Guide: Steps to Start Today and Mindful Living Meaning: Understanding Its Role in Wellness.